Dr Livingstone, I presume…

This article appeared in the Ely Ensign in November 2003 on page 11.

“This is the finest place I have known in all of Africa …an illusive place where nothin is as it seems …I am mesmerised.”

David Livingstone speaking about Zanzibar in 1866

In our September issue, we featured the two-week visit by members of our cathedral congregation to Zanzibar and Christchurch Cathedral built on the site of the island’s old slave market.

Zanzibar suffered more heavily at the hands of the Arab-dominated slave trade than anywhere else in East Africa.

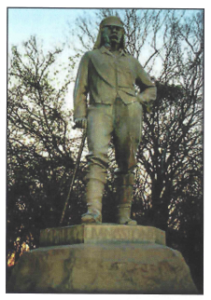

Perhaps this Tanzanian island’s most revered hero is Dr David Livingstone – Africa’s most famous missionary and anti-slave campaigner. His well-known speech at Cambridge Senate House, which led to the formation of the Universities mission to Central Africa, links his remarkable life to our region and diocese. Margaret Spencer-Thomas tells his story.

When you visit Zanzibar’s cultural centre, Stone Town, you will almost certainly come across Livingstone House on Guilioni Road.

Many European explorers used the building as a rest house. One of them was the doctor and missionary, David Livingstone.

Although he lived here for only a few months between 1865 – 66, this building now stands as a museum dedicated to his memory and has several of his papers and articles on display.

A crucifix hanging by the pulpit in Zanzibar Cathedral is said to be made from the wood of the tree under which Livingstone’s heart was buried. You can also see the house where his body was laid after it was brought fromZambia on its way to be buried at Westminster Abbey.

On our visit, our guide told me that most people in Zanzibar are descendants of slaves and so it is not surprising that Christians on this island venerate him as their hero.

Livingstone was born on March 13, 1813 in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, eight miles south of Glasgow. He was one of seven children in a distinctively Scottish family environment of personal piety, poverty and hard work. His family was poor and, at the age of 10, he was sent to work in a cotton mill. He studied at night school and went on to study medicine and theology at Glasgow University.

He first planned to become a medical missionary in China, but the Opium Wars made this a bad place for a westerner with good intentions. While he was still studying he med Dr Robert Moffat, a missionary who inspired him to go to Africa instead. After a four-month journey in 1841, he landed in Cape Town, in modern South Africa.

Once in Africa with Dr Moffat, he founded a new mission two hundred miles north of his assigned station. As a doctor and a missionary, he decided that the best way to teach Africans about Christ was to move about and see as many people as he could, using his medical skills to heal the sick and preaching the Gospel.

Livingstone was one of the first Europeans to explore the central and southern parts of Africa. He treated Africans with respect and believed the best way to share his faith with them was to teach them about the outside world. He learned their languages and customs, and explored a great part of the continent. During his early travels he was attacked and maimed by a lion, costing him the use of his left arm.

In 1845, he married Dr Moffat’s daughter, Mary. She, and later their three daughters and three sons, often joined Livingstone on his early explorations across the African wilderness.

Still, there were many times when they could not be together. The longest period of separation was for nearly four years between 1853 – 56. Livingstone completed one of the most amazing journeys ever undertaken – a coast to coast venture that covered four thousand miles of unexplored land, most of which was located along the Zambezi river.

Although he did not enjoy writing, Livingstone supported his missionary work by writing books and giving lectures about his travels. He returned to England for an extended visit and welcomed as a great explorer. Soon he was asked to give lectures about his experiences in Africa – telling the world about the slave trade, which he called “the open sore of Africa.”

In his famous speech at Cambridge Senate House in 1857, Livingstone set a strategy to open up Africa “for commerce and the Gospel”.

He said, “The people of Central Africa are very desirous of trading, but their only traffic is at present in slaves. It is therefore most desirable to encourage trading in other commodities, such as cotton. By encouraging the native propensity for trade, the advantages that might be derived in a commercial point of view and for the spreading of the Christian Gospel, are incalculable.”

He told his audience that he believed it was most important to find a path across the sea so that civilisation, commerce, and Christianity might find their way to Africa, and the slave trade would cease. He wanted to encourage Africans in cotton production, which he hoped would undercut American cotton and undermine American slavery.

He so challenged and inspired members of Cambridge University, that they founded what became the Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA). The universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Glasgow all gave him honorary degrees.

Returning to Africa, Livingstone and his wife began their last journey together. It was during this adventure that he faced the severest trail of his life; Mary died in 1862 from complications related to African fever.

Livingstone led an expedition to discover the sources of the Nile River and explore the watershed of central Africa. Little was heard of him during this period until he was met by a rescue party led by Henry Morton Stanley, who is said to have greeted the explore with the famous remark, “Dr Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley had been sent by the new York Herald Tribune newspaper to help, but it had taken a year to find him.

With Stanley’s supplies Livingstone continued his explorations, but he was weak, worn out and suffering from dysentery. Then, on the morning of April 30, 1872, his two African assistants found him dead, still kneeling at his bedside, apparently praying when he died. They dried his body and carried it and his papers on a dangerous 11-mount journey to Zanzibar, a trip of 1,000 miles. They natives buried his heart in Africa as he had requested, but his body was returned to England and buried in Westminster Abbey.

The slave trade was finally outlawed in Zanzibar in 1873.