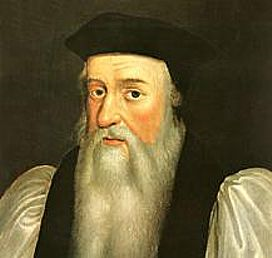

Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a supporter of King Henry VIII, established the first stage of the reformed English church. But, his work came to an end when he was imprisoned and martyred by the Catholic Queen Mary. Cranmer was a Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge. He is one of the great reforming figures of the English Church, and his legacy still endures.

Early life

Thomas Cranmer was born at the beginning of the Tudor period, in 1489. He studied at Cambridge and became a fellow of Jesus College and a Reader (the level below Professor) in Divinity in 1510.

However, the College forced him to resign his post following his marriage to his first wife, Joan, the daughter of a local tavern-keeper. After her death in childbirth, he became a fellow of the college once more and took holy orders in 1523.

Career

After a plague forced Cranmer to leave Cambridge for Waltham in Essex, his standing came to the notice of Henry VIII. The King and his councillors realised Cranmer was a willing advocate for Henry’s desired divorce from Catherine of Aragon. Cranmer argued the King’s case to Rome in 1530, and two years later became ambassador to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

He travelled to Germany to learn more about the Lutheran movement and met reformers on the continent. Among them was Andreas Osiander, a Lutheran reformer. During his visit he met Osiander’s niece, Margarete, and they were soon married. His marriage meant he had to set aside his priestly vow of celibacy.

In 1532, Cranmer was recalled to be Archbishop of Canterbury. However, at this time clerical marriage was illegal in England and he had to hide his marital status for a while. Once the Pope had approved his appointment, Cranmer declared Henry’s marriage to Catherine void. Four months later he married the King to Anne Boleyn.

Henry removed the Pope’s authority over the English Church but otherwise there was little reform until after the king’s death. Only then, under the reign of the boy king, Edward VI, was Cranmer able to lead a detailed and thorough English Reformation with the freedom to make the doctrinal changes he thought necessary to the church.

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer was the first compendium of worship in the English language. Cranmer was primarily responsible for the first edition in 1549 and its revision in 1552. Much of the familiar Prayer Book language derived from his own work. The words of the Lord’s Prayer, the creeds and the Morning and Evening Prayer canticles are mostly his.

The glorious translation of the Latin collects into prayerful and poetic English also owe much to him. These translations have, for over 400 years, been at the heart of English spirituality. Generations of worshippers have become familiar with these words through regular hearing, Sunday by Sunday. They still retain their beauty even in their modern modified form.

Cranmer maintained that a proper Christian Communion depends more on the heart of the practitioner than on the actual bread and wine used in the service. He also encouraged the public reading of the Bible by the entire congregation. Although his views can seem sensible to modern ears, at that time they were nothing short of revolutionary. His radical ideas provoked a storm of controversy, which was to bring about his downfall.

Queen Mary

When Edward became mortally ill in 1553, it became clear that he would die without an heir. He did not want the crown to go to his half sister, Mary Tudor, because he feared she would reverse Cranmer’s Protestant reforms and restore Catholicism. So, he attempted unsuccessfully to exclude her from the line of succession.

After Edward’s death, Cranmer supported Lady Jane Grey as successor. Her nine-day reign was followed by Mary, a staunch Roman Catholic loyal to the Pope. The arrival of the new Queen triggered a sustained struggle for the survival of Protestantism and Catholicism in England.

Mary blamed Cranmer for her mother’s divorce. She overturned his brief reform movement and deposed Cranmer together with most of her other Bishops. Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of London, and Hugh Latimer, Bishop of Worcester, were to face the same fate as Cranmer.

After a long trial and imprisonment, Cranmer was forced to sign an official document renouncing his reformist views. This document included a public proclamation of the Pope’s supreme authority and the physical presence of Christ in the bread and wine of Communion.

He eventually acknowledged Papal supremacy and the truth of Roman Catholic doctrines except for transubstantiation. Despite his recantation, he was convicted of heresy. He was sentenced to be burned at the stake in Oxford together with Ridley and Latimer.

Legacy

Cranmer was martyred in Oxford six months after the other two. As the flames began to rise, he dramatically stuck his right hand into the fire – the hand with which he had signed the renouncement of his beliefs.

He then cried out, “This hand hath offended!” With that gesture, the government’s hope of quelling the Reform Protestant movement was undone. Queen Mary may have won the battle, but Cranmer unknowingly won the war.

Close to the spot where, Cranmer, Ridley and Latimer died for their faith, there now stands the great Martyrs’ Memorial in the city’s Broad Street. The Church remembers Cranmer on 21 March, the day of his death in 1556.