John Stevens Henslow (1796–1861)

John Stevens Henslow was a brilliant botanist and geologist, an ordained priest in the Church of England and a generous philanthropist. He spent the former part of his working life in Cambridge, and made a lasting contribution within the city and the University. He made his name in the wider world as mentor to Charles Darwin. This article explores the remarkable life of this talented nineteenth century cleric and the contribution he made to science.

Contents

Henslow’s early life

Henslow was born on 6th February 1796 in Rochester, Kent. He was the eldest of eleven children. His father, a solicitor, encouraged him to develop his enthusiasm for natural history and, at a very early age, he became an avid collector of botanical specimens.

In 1814, Henslow entered St John’s College, Cambridge, where he studied science and mathematics. He graduated in 1818, renewed his interest in natural history and developed an interest in geology.

One of his Cambridge colleagues was Adam Sedgwick, one of the founders of modern geology. Together, they made geological expeditions to the Isle of Wight and the Isle of Man.

In 1821 the two men established the Cambridge Philosophical Society as a debating forum and means of exchanging knowledge in mathematics and the natural sciences. The following year, the University offered Henslow the chair of mineralogy which he took up with great enthusiasm.

Henslow’s career

Two years later he was ordained and, in 1825, became the curate at Little St Mary’s Church, Cambridge. In the same year, he accepted the position as Regius Professor of Botany – a post he held for the rest of his life.

At this time, the study of botany was at a low ebb in the University. His predecessor had been absent from his post for 30 years and no lectures had been given during this long period.

By contrast, the young and vigorous Henslow took up his professorship with a very different outlook. He was a lively, progressive teacher, both in the classroom and in the field. He pioneered the use of visual aids to enthuse his students. As a good artist, he was able to produce a range of colourful botanical wall charts and diagrams himself.

His natural enthusiasm soon made botany one of the more popular subjects at the University. Rather than pampering his students, he encouraged them to make their own observations. So, he gave them plants, encouraging students to examine and record their individual structural characteristics. He took them on field trips, and invited them to his house for dinner. There they discussed a range of scientific topics more informally.

A botanic garden for city and university

Henslow had few botanical resources within the University for his enlightened approach. The old herbarium was rapidly decaying, and the small Botanic Garden in the centre of the city was inadequate.

Henslow envisaged a new and bigger Botanic Garden able to serve two different communities. It was to become a place of scientific study for the University. But he also wanted a place of recreation and learning for the wider community. So he set about extending the site.

In 1830, he identified a 40-acre area of cornfields just south of the city boundary. Eventually, the University commissioned a botanic garden plan for the entire area.

Henslow supervised the the planting of new trees, shrubs and plants, many of which came from overseas. His two founding strands – University and community – remain enshrined in the research and public engagement that continues today in the Botanic Garden. He was its crucial founder, making it world-famous.

However, this academic clergyman was yet to play an even more pivotal role in the field of science.

Mentor to Charles Darwin

Today, historians best remember Henslow as friend and mentor to his pupil Charles Darwin, whom he inspired with a passion for natural history.

The two met in 1828. The young Darwin, who had enrolled to study theology at Christ’s College, began attending Henslow’s Friday-evening scientific soirées.

Henslow became his tutor and soon, he marked out Darwin as a promising student. In time, his star pupil would became a lifelong friend. Their remarkable alliance persisted in spite of Darwin’s eventual atheism and Henslow’s never-failing liberal Christian faith.

After Darwin’s graduation, Henslow persuaded him to study geology. In addition, he arranged for him to assist Adam Sedgwick and help with some research in north Wales. Soon Darwin would be putting his newly acquired skills to the test.

Henslow was offered a post as naturalist to sail aboard the survey ship HMS Beagle on a planned two-year trip to survey South America. However, his wife dissuaded him from accepting. Seeing a perfect opportunity for his protégé, the good-natured clergyman wrote to the ship’s captain, Robert Fitzroy. He recommended Darwin saying that he was an “acute observer” and the ideal man to join the expedition team.

Darwin sets sail

Just a few months later, Darwin set sail for the South Seas. In the end, this turned out to be a round-the-world voyage of nearly five years. It included a visit to the Galapagos Islands, where he discovered a host of unique flora and fauna.

During the Beagle voyage, Darwin and Henslow wrote to each other as often as the primitive postal system would allow. Henslow encouraged Darwin, and advised which specimens to collect, recommending the best way of preserving and shipping them.

As the main recipient of Darwin’s massive collection of scientific samples, Henslow passed them on to the appropriate experts to analyse. He published extracts of Darwin’s letters in scientific journals and presented summaries to the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

When, in 1836, Darwin returned home, Henslow helped him to obtain funding to publish his zoology books. By now his scientific credentials and future career were assured – thanks largely to Henslow.

More than twenty years later, Darwin was to publish his theory of evolution by natural selection. And thus, On the Origin of Species (1859) became one of the most controversial ideas of the 19th century.

Darwin described his meeting with Henslow as the one circumstance ‘which influenced my career more than any other’.

From university to parish priest

Although the two men continued their friendship, life for Henslow was about to undergo a dramatic change. In 1837 he became Rector of the parish of Hitcham in Suffolk. He remained there for the rest of his days. only returning to Cambridge to deliver his botany lecture courses.

Hitcham was a remunerative Crown living which paid its Rector well. But its parishioners were poor and most people would have been illiterate. Not surprisingly, the great university academic turned out to be an uninspiring preacher. His congregation was barely big enough to fill a single pew. So instead, he decided to concentrate on improving his parishioners’ well-being through scientific, rather than spiritual, enlightenment.

At this time, education had to be paid for. As a result, Henslow both raised funds and donated his own money to set up a school in 1841. He taught some of the lessons himself. Among his many books, he published a standard work on the flora of Suffolk. He identified the plants which the schoolchildren found growing in his parish. By 1860, he had recorded 406 species. A hundred years later, 60 of these could no longer be found.

Many of the children acquired considerable botanical knowledge, with some going on to become teachers themselves.

Other philanthropic initiatives

Henslow engaged in many other philanthropic endeavours. During the so-called hungry 1840s, severe economic depression and serious crop failures across Europe led to widespread famine. He reacted to the crisis by letting 52 allotments on land which was owned by the parish church.

However, local employers were furious at this use of glebe land. They took action and decided to refrain from hiring any labourers who rented an allotment. Even so, the scheme caught on and, two decades later, 150 allotments were under cultivation in the village.

Henslow founded the Ipswich Museum in 1847, becoming its president in 1850. He administered local charities, and organised educational excursions to various venues, including the 1851 Great Exhibition.

Henslow’s contribution to agriculture

The rapid population growth in nineteenth century Britain brought about the need for more intensive farming. Some scientists began experimenting with different chemicals in an attempt to develop fertilisers to improve the yield in agricultural crops.

Henslow applied his geological expertise as research interest began to focus on the chemical content of naturally-occurring rocks and minerals. He already knew that the Cambridgeshire greensand and river valleys in East Suffolk were abundant sources for phosphates.

In 1842 while on holiday in Felixstowe, he discovered coprolite nodules, fossilised animal faeces, in the nearby Red Crag cliffs. He analysed them and discovered they contained a high proportion of calcium phosphate.

As a result, he began field experiments to try out various fertilisers and measure the resulting product. He showed that coprolites were an alternative and cheaper source of phosphate and could be “a matter of commercial proposition”.

The fertiliser industry

Eventually, Henslow started writing articles in the local and agricultural press promoting the success of coprolites as a phosphate based fertiliser. And thus, Henslow’s discovery led to the growth of a major industry that revolutionised farming in East Anglia and beyond.

Although he derived no financial benefit, his discoveries played an important part in the establishment of the fertiliser industry. Famous names include Joseph Fison, who set up his works in Ipswich and a depot in Hauxton near Cambridge. Other beneficiaries from his research were the Prentice brothers in Stowmarket. Soon they were exporting superphosphates around the world from the port at Ipswich.

The oddly-named Coprolite Street in Ipswich marks the site where the phosphate nodules were brought to a building to be ground up and mixed with sulphuric acid. Local residents used to complain that the process made a terrible smell.

Henslow’s other scientific work was also far ranging. He showed Irish farmers, stricken by the potato famine (1845–46), how to extract starch from rotten potatoes. He also gave public lectures on the fermentation of manure. His discoveries spread far and wide.

Henslow’s last years

Henslow’s widely acclaimed achievements brought him in contact with many distinguished and prominent people. He kept in touch with the wider scientific community and, of course, his celebrated former pupil, Charles Darwin. He even tutored Queen Victoria’s children.

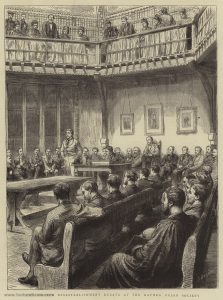

The year before his death, Henslow chaired the Great Oxford Debate on Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection. The event took place at the University Museum on 30 June 1860, seven months after the publication of his theory. Darwin himself did not attend.

The Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, used the occasion to uphold the idea of biblical creation. However, Henslow’s son-in-law, Joseph Hooker, and Darwin’s close associate, Thomas Huxley, successfully championed the new theory. Both sides claimed victory and the debate continues to this very day.

The following winter, Henslow became seriously ill with a heart condition. His health continued to grow worse. Realising that the end was near, with Hooker standing vigil, he bade farewell to numerous visitors called to his bedside. Conspicuous by his absence was Charles Darwin, by now a virtual invalid himself.

John Stevens Henslow died after a bronchial attack on 18th May 1861 aged 65. He is buried in Hitcham churchyard. Charles Darwin wrote to Hooker, saying, “I fully believe a better man never walked this earth.”